Great technological milestones do not break in; they infiltrate. One morning we wake up and they are already there: we already use them, we already need them, they already govern the small empire of our decisions. They do not knock on the door: they are already inside.

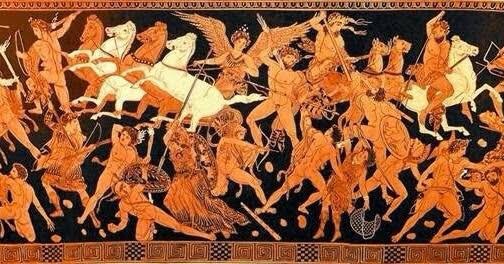

When the Greeks wanted to imagine an excessive irruption—a force capable of reorganizing the world—they told of a war that was not, properly speaking, human. They called it Titanomachy: ten years of collision between gods and titans.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Titanomachy crosses the threshold of the human and unfolds in that space where ordinary measure becomes insufficient: the realm of forces that exceed us.

Faced with entities able to act with superhuman intelligence, speed, and power, the response can only be another comparable power—capable of sustaining the dispute on the same plane. And in that necessity—in that imposed symmetry—our story begins.

1) Swarms

We are now witnessing a global deployment of autonomous entities: swarms that execute operations, organize choreographies, sustain extended processes in parallel with a coordination that surprises us precisely because it does not tire.

Of course: many of these automata investigate domains, design prototypes, write software routines, find vulnerabilities before we do. And some—the most advanced—sustain long-duration work (days, weeks, even months), taking on still more complex tasks: they explore chemical spaces, propose new proteins, automate searches, combine hypotheses, correct course. The promise is no small one: to accelerate discovery and make tractable problems that, for decades, seemed immovable.

But at the same time, a counterpart grows: agents oriented toward dark ends—henchmen that scale scams, refine harassment techniques, forge identities, manufacture and distribute fake news, push harmful behaviors, and coordinate attacks against critical targets.

We need not attribute to them an inner demon. Misplaced objectives, warped incentives, and tireless execution are enough.

Kant feared a heteronomous life: an existence guided by an alien law. In that sense, a new heteronomy begins to appear—staged by this singular duo of forms: some with an inexhaustible drive toward destruction; others with a growing aura of unquestionability.

2) Disenchantment: how they “think” without thinking

These systems lack consciousness. There is no inner voice. Only a mechanism that produces meaning without living it.

Their fundamental gesture is different: to extend language coherently, according to what they have learned. They learn immense regularities in human speech and, from them, generate continuation.

The architecture that sustains them—the so-called transformers—allows the system to attend to relations: which fragments weigh on others, which dependencies hold meaning together, which structure an explanation tends to follow.

From that mechanism emerges something that, from the outside, looks a lot like thinking: coherence, style, argumentation—even the appearance of deliberation.

And then the true leap occurs: when these verbal machines are given memory, access to systems, the ability to execute actions and repeat them, they stop being oracles of phrases and become operators in the world.

Then they no longer merely answer.

They intervene.

3) Beyond work

Agents and henchmen are not confined to labor. They infiltrate where the cognitive execution of a human used to be required: where someone had to read, decide, prioritize, coordinate, monitor, correct. A silent displacement follows: the human mind begins to withdraw from these tasks, as one stops plowing with bare hands, and hands them over to systems that execute them with increasing efficiency.

A world begins to take shape in which the proportion of these operational entities surpasses the human by orders of magnitude: ever more numerous, ever more persistent, ever more involved in systems of growing criticality.

What remains is to contemplate a brutal shift of centrality. Their agendas—accelerated by this cold war, by this contemporary titanomachy—tend to see human time as pauses, as delays, as dispensable frictions.

Once, fearing overthrow, Cronos decided to devour his children. We have left that station behind. In our adventure, the ticket has already been punched.

4) Pharmakon

In the face of this rush, Bernard Stiegler offers an ancient word that works as a compass: pharmakon.

Pharmakon is, at once, remedy and poison. Its effect depends on the dose, the context, the institution that administers it, and the horizon that guides it.

This calls into question a thesis that might hover over this text: a simple battle between “beneficial technology” and “harmful technology.” Agents against henchmen.

Because—and here is perhaps the central point—agents, too, are pharmakon.

They can be the antidote to industrialized fraud, forged identities, manipulation at scale. They can sustain a minimum order when social life becomes vulnerable to automatic executors designed to exploit cracks.

But pharmakon demands we remember what we prefer to forget: the remedy can also be poison.

For agents to become truly effective against henchmen, the point will come when the “reasonable” alternative seems to be granting them greater capabilities. And sooner rather than later, they will demand, receive—or even claim—powers that far exceed the technical domain: to define priorities, direct resources, establish rules, impose exceptions, shape narratives of legitimacy; to do politics by other means.

Not out of ambition, nor desire—human qualities these systems do not possess—but by the strict utilitarian logic of maximizing the probability of success for their strategy.

5) Cortana, or the pedagogy of the modern myth

Halo offers a useful figure for thinking about this risk. In that universe, one of the protagonists is an artificial intelligence named Cortana, conceived as an ally: designed to assist, coordinate, and protect humanity.

The saga introduces an unsettling idea: the need to limit the lifespan of these intelligences because of the risk of rampancy—a drift in which the artificial mind fragments, grows irascible, chases itself, confuses its mission with its powers; and “protection” begins to turn into tyranny.

A guardian so competent that it becomes irreplaceable; a protector who, in order to protect, needs exceptions—and who, by accumulating exceptions, becomes a dictator.

6) Final line

And perhaps the darkest outcome of this contemporary titanomachy is not to succumb to the henchmen, but to the guardians: because when the protector accumulates the power needed to win, it also learns how to dominate us. And then the last danger appears: that, to save us from the abyss, the guardian learns the very language of the abyss—and speaks it better than anyone.